- Research

- Open access

- Published:

A functional study of event-existentials in Modern Chinese

Functional Linguistics volume 1, Article number: 7 (2014)

Abstract

It is held that existentials in Chinese express the existence of things rather than events. We propose the term event-existential, in contrast to thing-existentials, to capture those clauses whose existents are obviously events. These include the so-called pseudo-existentials, clauses with the possessor as subject and the possessed as object, (dis)appearance existentials, etc. Though the two types of existentials are both composed of "NGL ^ VG ^ NG", the syntax is different. In thing-existentials, the clause-final NG constitutes the existent, whose existence is expressed through the configuration of the three elements as such. In event-existentials, the configuration of "VG ^ NG" expresses the event, whose existence is then asserted through its alignment with the clause-initial NGL. Apart from existence, event-existentials show the semantic features of eventuality, impersonality, and ergativity. The two types of existentials form a continuum, each occupying a pole and relating to the other through different degrees of thingness/eventuality, i.e., different degrees of prominence of the clause-final NG and the clause-middle VG and of the integration of the two.

About the term of existential

The term existential in Chinese is first put forward by Lü (1943). He defines the existential in terms of meaning, which is quite different from what is meant by the term today. Later on, Lü (1946) redefines existentials as clauses expressing the meaning of existence and (dis)appearance. Since the 1950s, the existential as a special syntactic construction has been much discussed, with new insights appearing from time to time. The frequently addressed topics include its definition, scope and classification, the semantic and syntactic features of the three components of the existential, i.e., the locative nominal group (NGL), the verbal group (VG), and the nominal group (NG) in that order. In recent years, new observations are made with the application of generative linguistics, functional linguistics, and cognitive linguistics to the study of the construction.

This study reviews the discussion on the scope and classification of existentials and proposes the term of event-existential, in contrast to thing-existential. The former captures a few constructions that are related to the latter; the two types of existentials are alike but different. We will try to bring out the semantic and functional features of event-existentials by drawing on Systemic Functional Grammar.

Lei (1993) holds that both meaning and structure should be taken into consideration when classifying and defining the scope of the existential. On the one hand, not all clauses expressing existence can be taken as existentialsa:

-

(1)

is an existential whereas (2) is not, though they both convey the meaning of existence. On the other hand, some constructions may share some syntactic features with the existential, but they should not be regarded as such:

Lei (1993) lists three conditions for a clause to be called an existential: 1) Semantically, it asserts the existence of something, that is, there exists something (New) in someplace (Given). 2) Syntactically, it observes the sequence of "NGL ^ VG ^ NG". And 3) the VG can be replaced by yǒu. Shao et al. (2009: 146) consider the existential as a special construction in Modern Chinese and they agree that both semantic and syntactic considerations are necessary in defining the existential. Zhang (2009: 243) recognizes the pragmatic characteristics in addition to the semantic and syntactic ones. That is, the existential typically functions to introduce a new entity into the discourse, which will be elaborated on in the text that follows.

Chen (1957) proposes the term (dis)appearance existentials:

Chen (1957) explains that such clauses resemble existentials: they both can be analyzed into the three elements of "NGL ^ VG ^ NG". Notionally, appearance and disappearance are the beginning and the end of existence respectively. Therefore, they can be taken as existentials in that they asserts the existence of something instead of representing actions or behaviours. Song (2007) distinguishes existential clauses from clauses of (dis)appearance, both of which can be subsumed under the term cúnxiànjù (clauses of existence and (dis)appearance).

We think that it is implausible to take clauses of disappearance (e.g., (5)) as a kind of existential, though they share some syntactic features with existentials. For one thing, disappearance and existence are simply different meanings. The communicative intent of the existential is to assert existence, which is presupposed in clauses of disappearance. To say that existence can be asserted through disappearance is to put the cart before the horse. For another, pragmatically, such clauses are not used to introduce new entities into the discourse, as existentials typically do. A simple examination of the construction (e.g., ……sǐle yígèrén. (死了一个人, "a person died in …") in the Corpus of Modern Chinese, Centre for Chinese Linguistics, PKU shows that none of the tokens yielded serves the function of introducing new entities into the discourse. This shows that it is questionable to take clauses of disappearance as a subtype of existential.

Another much addressed and controversial issue concerns the distinction between dynamic and static existentials and the so-called pseudo-existentials. Fan (1963) regards such clauses as (3) and Chuāngwài piāozhe dàxuě ("It’s snowing heavily outside the window.") as dynamic. She observes that "the verbs in these clauses can be preceded by such progressive markers as zhèng or zài, to denote ongoing processes". In the same vein, Song (2007: 16) defines dynamic and static existentials according to whether the verb in the clause expresses a state, an action, or an ongoing process. But the notion of dynamic existentials is controversial. Fan (1963), Zhang (1982), Li (1986), and Dai (1988) think that (3) is a dynamic existential; whereas Zhu (1980) and Lei (1993) object to including such clauses into existentials merely on the grounds of syntactic similarities; without taking semantics into consideration. Song (1988,2007) shows how (6) and (7) are different:

According to Song, the VGs in (6) (zuòzhe) and (7) (pǎozhe) denote a state and a dynamic action, thus rendering the existentials static and dynamic respectively. He further explicates that (6) and (7) are different from (3); the former belong to existentials while the latter does not. Lu (1997: 24–26) shows how (3) and (6) are different in structure and in semantics through transformational analysis and he attributes the differences to the semantic structure of the verb. Thus, it is realized that, though (3) is syntactically similar to the existential, it is not an existential. Song (1988) coins the term pseudo-existential to refer to it. But this term just shows that they are not real existentials; it does not tell us the defining characteristics (either semantic or syntactic) of the clause, neither does it explicate how it is related to the existential.

Another type of related clause is the one with the possessor as subject and the possessed as object (PSPO clause) (Guo1990), as exemplified by:

Li (1987) has noticed the similarities between (8) and the existential. After a diachronic survey, Shi (2007) comes to the conclusion that (8) derives from the existential, to which it still belongs. Lin (2008: 76) observes that Wáng Miǎn in (8) is the locative subject, rather than experiencer of the event. Therefore it is not essentially different from the existential. Li (2009) puts forward the term occurrence clause to cover both clauses of (dis)appearance and PSPO clauses. It means that "some event occurs in some place". Ren (2009) probes into the similarities between the semantic categories of "possession" and "existence and appearance" and the relatedness between existentials and such clauses as (8) by drawing on the theory of construction grammar. Zhang (2012) posits that clauses such as (8) and existentials exhibit a kind of isomerism as a result of the semantic extension of the verbs in question. They share common features in word order, in the argument structure of the verb, and in semantics. These are believed to be semantically and functionally motivated. But the relatedness of the two constructions and the motivations behind need be further investigated.

In the literature, a commonly held opinion is that the verb in the existential can be replaced by the typical existential verb yǒu (Fan1963, Lei1993, Song2007: 99–100). But when this happens, the meaning may be radically changed, though the resulting clause remains grammatically acceptable. Compare (9) and (10):

Though the existence of the oil lamp is expressed in both (9) and (10), it is asserted in the latter and entailed or even presupposed in the former. (9) asserts the oil lamp’s state of being lighted. This is more evident in (11):

-

(11)

asserts the rolling of beads of sweat, rather than the existence of them.

With regard to such controversies and problems in the literature, we put forward the term event-existential. In what follows, we will discuss the scope of event existentials, their functional/semantic features, and the continuous relationship between thing- and event- existentials.

The scope of event-existentials

Lyons (1977: 442–445) distinguishes three types of entities: first-order, second-order, and third-order entities. Generally speaking, first-order entities are physical objects such as animals, people, plants, artifacts, e.g., dog, woman, tulip, and car. The ontological statuses of these entities are relatively stable from a perceptual point of view. They exist in three-dimensional space, at any point in time, and they are publicly observable. Second-order entities are events, processes/activities, and states; they are what are referred to as "states of affairs". These entities are located in time and are said to occur/take place. Third-order entities are abstract; they are outside both space and time. These include facts, concepts, ideas, possibilities, and propositions (Lyons1977: 442ff, Vendler1967/2002: 242, 244, 246, Dik1997: 136).

We adopt the term events fromVendler (1997/2002) and Peterson (1997: 7, 81) to refer to second-order entities in Lyons’ terms and states of affairs in Dik’s (1997) terms. This is a cover term including actions, activities, situations, conditions, processes, etc., which can be predicated by such verbs as occur, last, begin, end, cause, etc. (Peterson1997: 92).

In Chinese, existentials not only assert the existence of things, but also that of events. However, it is taken for granted that they are only to express the existence of things. On the other hand, there are those clause patterns that are formally similar to the existential, but the existents in them are not things but events. The so-called pseudo-existentials (e.g., (3)) are cases in point.

There are three authors who have discussed event-existentials, though the terms they employ are different. Lin (2008: 74–76) finds that the following two clauses are different:

-

(12)

is an existential clause, whereas (13) is an occurrence clause, which expresses the occurrence of an event. According to Lin, yǒu and fāshēng are both light verbs and they both take locative nominals as subjects. In existentials, the locative element denotes the place where something exists. But in occurrence clause, it does not necessarily refer to the setting where the event in question occurs, e.g.:

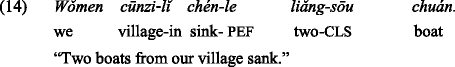

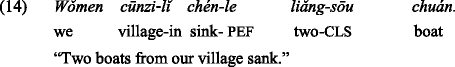

Lin (2008: 76) notes that the above example expresses that the event of the sinking of two boats occurred and that wǒmen cūnzilǐ ("our village") is not the place where the sinking occurred; it denotes the entity affected by the event. He (Lin2008: 76) thinks that (8) is a clause of occurrence, with Wáng Miǎn as the locative subject. But Lin (2008) is an exclusive study of the locative subject in Chinese. He only mentions occurrence clauses in passing.

Li (2009) throws doubt on plausibility of clauses of disappearance as a sub-type of existentials, for she finds they seldom occur in actual texts. Even with those few examples, it can hardly be said that they express the disappearance of something:

Li’s (2009) investigation shows that such clauses are not employed to convey the meaning of "there (dis)appears something in someplace", but to assert the occurrence of certain events. Occurrence includes the meaning of (dis)appearance, but it is not restricted to it. Li suggests the term clause of occurrence in contrast to clause of existence. The former includes such clauses as (3) and (8), and parts of traditional existentials. However, she does not formally define the term, neither does she explicate its domain or how it is related to traditional existentials. What’s more, though the term occurrence caters for the meaning of "VG ^ NG", it does not take into consideration the whole construction (see (22)). We hold that different configurations convey different meanings, and that the clause initial NGL is obligatory for the whole clause to be called an event-existential.

In English, there is not such a distinction between thing- and event- existentials; the same construction (i.e., there-existential) can be used to assert the existence of both types of entities (Halliday2004: 256):

Of the above three examples, (17) expresses the existence of things (i.e., aboriginal paintings that tell the legends of this ancient people), and (18) and (19) that of events (i.e., comparable political campaign and confusion, shouting and breaking of chairs respectively). Halliday (2004: 258) writes: "In principle, there can ‘exist’ any kind of phenomenon that can be construed as a ‘thing’: person, object, institution, abstraction, but also any action and event…" In English actions and events can be nominalized as things. But this is not available in Chinese, where existence of second-order entities has to be conveyed through processes. Compare:

Event-existentials resemble thing-existentials in having the following syntactic configuration:

Semantically, the former expresses occurrence of events or existence of states. The prototypical process for thing-existentials is yǒu and that for event-existentials is fāshēng (Tao2001: 151). The probe for thing-existentials is: What is there (in NGL)? That for event-existentials is: What is happening there (in NGL)?

The examples discussed above, including (5), (8), (9), (13), (14), (15), (16), and (20), are all event-existentials. Some of them are considered thing-existentials, others PSPO clauses, still others dynamic existentials or clauses of (dis)appearance in previous studies. We will show how each of them fit into event-existentials.

We begin with so-called pseudo-existentials. These are exemplified by (3) and (20). Since they look like thing-existentials (both share the structure of (22)), they are often treated as such (Song2007: 98). But they are not. Fan (1963) brings out their difference through yǒu replacement (cf. Zhu1980: 64, Lu1997: 24–26), which can be applied to thing-existentials:

But this cannot be applied to event-existentials, e.g.,

The yǒu-replacement test is valid in showing that clauses such as (3) are not real existentials. Along this line of analysis, we cannot help but ask: What are pseudo-existentials, if they are not genuine existentials (i.e., thing-existentials)? How do we explain the differences between them? The concept of event-existentials can help answer these questions. The existents in event-existentials are not things, but events. (3) is not to assert the existence of xì, but the happening of the performance or the singing of it. Both types of existentials express existence by virtue of the configuration of the initial NGL and the two following elements, though the latter are different in meaning (see the next section).

Second, PSPO clauses are also event-existentials. Apart from (8) and (14), (24) is another example.

As we reviewed in the preceding section, some scholars notice that such clauses are related to existentials; they even believe that they belong to existentials. However, it is evident that (8), (14), and (24) are not to assert the existence of fùqīn, liǎngsōu chuán, and kèrén. Rather they express the meanings that the events of "father died", "two boats sank", and "guest came to visit" occur to Wáng Miǎn, cūnzi, and Xiào Zhǎng respectively. On the other hand, Wáng Miǎn and fùqīn, cūnzi and liǎngsōu chuán, and Xiào Zhǎng and kèrén stand in a relationship of possessor and possessed respectively. Cross-linguistically, possession is not inherently different from location. To be specific, possessors are locative. They may take such case forms as locative, adessive, or prepositions and locative words; these are locative in nature (Lyons1967, Clark1978: 118, Freeze1992, Zeitoun et al.1999, Baron & Herslund2001, Abdoulaye2006, Peeters et al.2006, Wang and Zhou2012, Wang and Xu2013). This explains the relatedness of existentials and PSPO clauses: In both constructions, the clause-initial NG is locative, and they both express existence, with the existent being things in the former, and events in the latter.

Similarly, clauses of disappearance (e.g., (5)) are event-existentials, for the simple reason that they express existence/occurrence of events rather than things. Finally, it should be pointed out that, as the above discussion suggests, thing existentials do not constitute a homogeneous category. Those existentials whose processes are realized by verbal groups other than yǒu denote the occurrence/existence of event to some extent. Thing-existentials and event-existentials form a continuum. This is what we will elaborate on in the following two sections.

Functional analysis of event-existentials

As we have shown, thing- and event- existentials share the structure of (22), and they both express existential meaning by virtue of the configuration of the clause-initial NGL and the following VG and NG. Their major semantic difference lies with the existent. In thing-existentials, the existent is realized by the clause final NG. But the realization of the event meaning needs some explication.

As we have shown above, (5), (8), and (20) are not to assert the existence of kèrén, fùqīn, and huì respectively. These realize the event meaning zǒule kèrén ("guest left"), sǐle fùqīn ("father died"), and kāihuì ("have a meeting") when configured with the VGs in question. This is even more explicit in (20), where huì is not a thing by nature. Its function is to realize the event meaning of "have a meeting" when combined with the verb kāi. The event functions as the existent in event-existentials.

The nucleus of an event is the process realized by the VG. It is indispensable to the event. This explains why the VG in event-existentials can neither be omitted nor replaced by yǒu (see section "The scope of event-existentials")b. Furthermore, in some cases the clause-middle VG and clause-final NG are so closely integrated that they cannot be separated from one another and form one word in the language, e.g., chàngxì in (3) and kāihuì in (20).

Tables 1 and2 show the differences between the two types of existentials.

As is shown in Table 1, thing-existentials can be analyzed into three semantic elements: Location ^ Process ^ Existent. They are realized by NGL, VG, and NG (denoting the thing) respectively. With event-existentials, the analysis is of two levels as is shown in Table 2. At the first level, the clause is a configuration of "Location ^ Existent", realized by the NGL and the Event in that order. At the second level, the Event is further analyzed into "Process ^ Range" by virtue of the fact chàngzhe and xì are highly integrated and the latter is not so much a participant of the process as a refinement and specification of it (Halliday2004: 295)c. That is to say, the Process and the Range do not play any direct role in the whole clause; they function by constituting the Event. The latter configures with the Location in the clause (cf. Yutaka2001).

To express the existence of an event in a location, two semantic elements must be present: an event and a location. The former is expressed by "VG ^ NG", and the latter NGL. The configuration of "NGL ^ Event" expresses the meaning of "there exists/occurs some event in some place". In this light, event-existentials are genuine existentials rather than pseudo ones.

Another semantic feature of event-existentials is impersonality. This feature distinguishes event-existentials as a type of uncanonical clause from canonical ones. The latter is exemplified by:

In canonical clauses, the actor occupies the clause-initial position and it functions as the subject as in (25). In event-existentials, the actor is deleted or demoted to some less salient positions than the subject (Yamamoto2006, Afonso2008, Siewierska2008). For example, in (3) and (8), the Actor (i.e., the singer) and the Behaver (i.e., fùqīn) are omitted and demoted to the end of the clause respectively. As a result, they take on an impersonal feature. In terms of transitivity, only one participant is allowed in event existentials. If the process is transitive, the actor is omitted and the only participant is the Range as in (3). If the process is intransitive, the only participant (e.g., Behaver in (8)) is demoted to the clause-final position.

There are also such event-existentials where there is not any direct participant; the process alone realizes the event as in (20), in which kāihuì ("have a meeting") is a VG realizing the process. This analysis can also be applied to (3), for chàngxì ("sing opera") can be taken as a VG realizing the process. This proves our point that the VG and the NG in event-existential are highly integrated such that they form a verbal group. Event-existentials are different from canonical clauses. They are not so concerned with the transitive relationship between participants as with occurrence and existence of states of affairs. The message they convey is not who does what to whom but what happened (Davidse1992,1998; Halliday2004: 284–285). The syntactic choice and configuration help impersonalize the event, which seems to happen by itself, without being instigated by any agent. Thus impersonalization and the meaning of existence and occurrence are in tune with each other.

The discussion so far points to the third semantic feature of event-existentials, i.e., ergativity (cf. Wu2006: 129–131). According to Halliday (1968: 182), transitivity and ergativity are two complementary systems suited to construing different aspects of meaning (cf. Lü1987, Dixon1994, Davidse1998). Different languages may prefer the one over the other. Accordingly transitivity analysis and ergativity analysis are to be employed to bring out the respective semantic resources behind (Davidse1992: 132,1998). When we apply transitivity analysis to (25) and ergativity analysis to (3), we have Tables 3 and4.

Transitivity analysis fits well with (25), which contains both the obligatory elements of a behavioral clause and which constitutes an answer to the probe: What is Zhang San doing on the stage?. If we analyze (3) in terms of transitivity, the result will be clumsy, for the obligatory element of the Behaver is absent. Therefore it cannot be taken as an appropriate answer to the probe. On the other hand, ergativity analysis of (3) makes explicit its communicative intent. It caters to the probe: What is happening on the stage? (Davidse1992,1998; Dixon1994: 214–215).

Halliday (2004: 284–285) notes that

"Happening" means that the actualization of the process is represented as being self-engendered, whereas ‘doing’ means that the actualization of the process is represented as being caused by a participant that is external to the combination of Process + Medium. This external cause is the Agent.

In the transitivity model, the nucleus is "Agent ^ Process"; the process may or may not extend to another participant, that is, the Goal, so that there are transitive and intransitive clauses. In the ergativity model, "Process ^ Medium" forms the nucleus (Halliday1994: 163). Ergativity interpretation of event-existentials spells out the functional configuration of different elements within it, so that the event is represented as happening by itself.

As has been clarified, the only direct participant of the process in event-existentials is either the actor (if the process is intransitive), or the goal (if the process is transitive), or other roles depending on the type of process involved. These are all called Medium in ergative analysis; they are entities through the medium of which the process comes into existence (Halliday1994: 163). Thus, (5) can be analyzed as Table 5.

Yìbāng kè is the Medium through which the event of leaving takes place. The Medium is the only essential elements for the process to be able to take place. Thus, yìběn hòuhòude měilìde cídiǎn in (4), yìbāng kè in (5), zhǔxítuán in (6), qìchē in (7), fùqīn in (8), yìzhǎn yóudēng in (9), yìkēkē hànzhū in (11), liǎngsōu chuán in (14), yígè wǎn in (15), yíliàng chē in (16) and kèrén in (24) are all Mediums.

The other participant involved in event-existentials is Range. This is the participant role that specifies the range or scope of the process (Halliday1994: 146). The Range in event-existentials is not an entity; it defines the process (ibid.). For example, in kāihuì in (20), huì ("meeting") is the Range. This is not an entity; there is no such thing as meeting other than the acting of having (kāi) it. The process and the range are integrated (and are realized by one lexical item), they collectively express the same event. Thus Halliday calls it "process Range" (cf. Halliday1994: 146–147). We propose the analysis of "Process/Range" (i.e., the Process conflates with the Range) if they are realized as one lexical item and are unanalyzable. Examples (3) and (20) are cases in point. Table 6 is the analysis of (3).

For those examples where the Range is more elaborated and is realized as a separated lexical item, the analysis of "Process ^ Range" will be more appropriate. This applies with Examples (13) (Table 7).

The NGL in event-existentials, can be analyzed as Setting Subjects (Langacker1991: 345–348): they are pseudo-participants with a functional affinity to circumstances. Experientially, it denotes the Location; its function is to locate the event denoted by "Process ^ Medium/Range", with regard to some location expressed by itself.

According to Halliday (2004: 287), "in a more abstract sense, every process is structured in the same way, on the basis of just one variable. This variable relates to the source of the process: what it is that brings it about. The question at issue is: Is the process brought about from within, or from outside?" With respect to this variable, he recognizes two types of clause in terms of ergativity, i.e., ergative and non-ergative clauses. In the former the source is explicated, while in the latter it is not (cf. Davidse1998: 102–105). Thus, non-ergative clauses are employed to express happenings, especially when the cause is not clear. Event-existentials are non-ergatives; the cause of the event (i.e., agent/instigator) is suppressed, so that what is presented is the happening, rather than what causes it to happen. This explains why there is only one direct participant in event-existentials, or even there is no participant at all: Only the process or process and medium/range are present for expressing the event. The whole clause communicates the existence of the event through the configuration of "Location ^ Event".

Continuous relationship between the two types of existentials

The term event-existential is proposed in contrast to that of thing-existential. This does not mean that the two types of existentials are discrete categories with a clear-cut borderline between them. Rather, they form a continuum, each occupying a pole. Within each category, the members are not homogeneous. They contain different sub-categories, showing different degrees of eventuality and thingness. For example, there are static and dynamic existentials within thing-existentials. Song (2007: 59) finds it hard to decide whether such clauses as the following should be subsumed under the one or the other without being arbitrary:

This heterogeneous feature also holds true for event-existentials, which, as we have discussed, comprise different subtypes, i.e., pseudo-existentials, clauses of (dis)appearance, PSPO clauses. They fade into the other pole towards thing-existentials. The continuous relationship between the two types of existentials is evidenced in the following clause, which can be read as either (see the following discussion):

In the remainder of this section, we will elaborate on the continuous relationship by locating different types of thing- and event-existentials along the continuum. At the pole of thing-existentials are static existentials, which gradually give way to dynamic existentials, clauses of (dis)appearance, and PSPO clauses, until reaching the other pole, that of event-existentials, typically represented by pseudo-existentials (Figure 1).

This continuum can be seen as diminuendo-crescendo from thingness to eventuality or vice versa, depending on from which end one starts. Typical thing-existentials exclusively express the existence of things. The clause-middle process is realized by the verbs yǒu and shì (e.g., (10)). These are light verbs (Huang1998, Lin2008: 74–76). They are non-salient and usually do not take aspect or tense markers; their main function is to link the location to the existent. The clause final NG, which realizes the existent, is comparatively salient. It often takes numerals and classifiers as premodifiers. Shen (1995) calls such NGs bounded (cf. Yutaka2001). This sub-type of existentials carries the strongest thingness.

There are other static existentials whose processes are realized by VGs other than yǒu and shì, e.g.,

Apart from expressing existence, such existentials also indicate the means of existence (e.g., guàzhe in (28)). The VG takes such aspect markers as zhe and le. The whole clause takes on some eventuality.

Eventuality increases in dynamic existentials, in which the existential meaning fades into presupposition, and dynamicity rises into assertion.

Example (29) expresses not so much that "there are wild chrysanthemum blossoms in the autumn wind" as that "chrysanthemum blossoms are swaying in the autumn wind". The process is obviously dynamic. It does not only take the aspect markers -zhe and -le, but also can be premodified by zhèng and zhèngzài d. On the other hand, the clause-final NG often does not take numerals and classifiers as premodifiers. All these show that, compared with static existentials, dynamic existentials are losing thingness and gaining eventuality (Song2007: 49–57)e.

Eventuality is even more evident in clauses of (dis)appearance (e.g., (4) and (5)). As the term (dis)appearance suggests, its primary experiential function is not to assert existence, but (dis)appearance, though the former might be its presupposition or entailmentf. (Dis)appearance is eventual by nature. The VG often takes the perfective marker -le. This shows the strong bounded nature of the process, and the prominence of the event denoted by the process (Shen1995,2004). This also holds for PSPO clauses. In general, it can be said clauses of (dis)appearance and PSPO clauses exhibit stronger eventuality and weaker thingness than dynamic existentials.

Eventuality is the strongest and thingness is the weakest in pseudo-existentials (e.g., (3) and (20)). The VG and the NG are closely integrated with each other, and they collectively express events instead of things. As is with dynamic existentials, the VG is highly dynamic and prominent in that it can be premodified by zhèng and zhèngzài and it takes the perfective marker -zhe. Correspondingly, the clause-final NG is unbounded and non-salient in that it does not take numerals and classifiers as premodifiers (Wu2006: 89). Here, as in all other cases, the diminuendo-crescendo of the two kinds of prominence is in perfect trading-off and cooperation.

As we have suggested above, the continuous relationship between the two types of existentials also finds expression in the degree of integration between the clause-middle VG and the clause-final NG. In yǒu/shì-existentials, the verb is semantically non-salient; it only functions to link the clause-initial NGL and the clause-final NG. But the link is loose in that lengthy premodifiers can be inserted before the NG (Song2007: 12, 79). It is only true with such existentials that the clause-middle yǒu/shì can be omitted, without radically changing the meaning. In other static and dynamic existentials, the VG and the NG are more closely integrated. In many cases, the NG is a bare noun so that the VG and NG are juxtaposed next to each other, without any element in between. Compared with static existentials, dynamic ones have a more integrated configuration of "VG ^ NG". And it is less likely for there to be any insertion (Song2007: 71).

In pseudo-existentials, the two are mostly closely integrated so much so that they sometimes form a single word or an idiomatic expression as in (3) and (20). This is the only subtype that does not allow any insertion of numeral and classifier between the VG and the NG in order for the clause to be grammatical (Fan1963: 395, Wu2006: 89):

Shen (1995) also notes that the NG disallows any numeral-classifier as premodifier. He takes (27) as representing a dynamic activity, i.e., the action of mounting cannons is taking place on the mountain, rather than the static existence of some cannons on the mountain. Pào is the Range of the Process jià. Thus (27b) is ungrammatical.

On the other hand, if the NG takes numeral-classifier as premodifier, the NG will become bounded and much more prominent. Thus, the link between the VG and the NG becomes relatively loose and thingness will increase, as shown in the following two examples:

Wu (2006: 45) notes that the VG and the NG in pseudo-existentials form integrated words or word groups, while those in dynamic existentials stand in a verb-object relationship to one another. In functional linguistic terms, the former are "Process ^ Range", while the latter are "Process ^ Medium". The former constitutes a closer integration, both serving the function of expressing the process (Halliday1994: 146).

In general, the continuous relationship between the two types of existentials lies in the trading-off between thingness and eventuality. The prominence of the one means the obscurity of the others, and vice versa. The prominence and obscurity are the fullest at the two poles.

Conclusion

The existential in Chinese is a much-addressed topic because of its particular syntactic and semantic features. Since the 1950s many achievements have been made in the definition, scope clarification, and classification of this construction. There are new insights appearing from time to time. These include the distinction between dynamic and static, genuine and pseudo-existentials, and the metaphorical extension on typical existentials. But there also exist some problems. For example, in discussing the semantics, previous literature does not distinguish the cases where existence is the asserted meaning from those where it is the presupposition or the entailment. A clause should not be taken as an existential because it presupposes the existence of some entity, for such a presupposition is present in most clauses other than those where existence is asserted. Another often-ignored distinction is that the existent in the existential may be either a thing or an event.

In order to account for a group of clause patterns which are closely related to the existential, but which are not its typical members, we put forward a new term, event-existential, in contrast to thing-existential. The former includes the so-called pseudo-existentials, PSPO clauses, dynamic existentials, and (dis)appearance existentials. They all express existence of events, rather than things. The two types of existentials share the structure of "NGL ^ VG ^ NG", though the semantic configurations are different: In event-existentials, the VG and NG express the event, whose existence is expressed through its configuration with the clause-initial NGL. Therefore, event-existentials show the semantic features of existentiality and eventuality.

There is only one direct participant in event-existentials; this is either the actor if the process is intransitive or the goal or range if the process is transitive. With the instigator of the event omitted or demoted to the end of the clause, the subject function is left to the NGL. This renders the clause impersonal.

Another feature of event-existentials is ergativity. Functionally they can be analyzed into "Location ^ Process ^ Medium/Range". This fits well with the ergative pattern.

These four semantic features are coordinated and unified within the same clause. It expresses the existence of events (not things), rather than the transitive relation of who does what to whom. Finally, there is not a clear-cut borderline between the two types of existentials. Rather, they form a continuum. The continuity finds expression in the diminuendo-crescendo of thingness or eventuality, the prominence of the process or the clause-final medium/range, and the degree to which the two are integrated.

Endnotes

aList of abbreviations: CLS = classifier, PEF = perfective, PRG = progressive, RED = Reduplication.

bIf we change (8) into WángMiǎn yǒu fùqīn. ("Wang Mian has a father."), by replacing sǐle with yǒu, the meaning of (8) will be drastically changed, with presupposed meaning being brought to the forefront and becoming the asserted meaning.

cApart from Range, there is another function that the NG may realize, i.e., Medium. (See the following discussion.)

dAccording to Chen (1999), scope of -zhe and zài are different, though they both express progressive aspect. -Zhe is restricted to the verb itself; it indicates a homogeneous, continuous and repetitive situation. Whereas the progressive meaning of zài exerts over the entire VG; it expresses an ongoing activity and it is highly dynamic (cf. Fan2007: 91).

eAccording to Song (2007: 71), most of the NGs in static existentials usually take numeral-classifier premodifiers; but the majority of the NGs (65%) in dynamic existentials do not take such premodifiers.

fThe existential meaning is the entailed meaning of clauses of appearance. For example, (4) entails the existence of yìběn hòuhòude měilìde cídiǎn. It is the presupposed meaning of clauses of disappearance. For example, (5) presupposes the existence of yìbāng kè. (See Note b.)

References

Abdoulaye M: Existential and possessive predications in Hausa. Linguistics 2006,44(6):1121–1164.

Afonso S: Existentials as impersonalizing devices: the case of European Portuguese. Transactions of the Philological Society 2008,106(2):180–215. 10.1111/j.1467-968X.2008.00192.x

Baron I, Herslund M: Introduction: Dimensions of possession. In Dimensions of Possession. Edited by: Baron I, Herslund M, Sørensen F. Amsterdam: Benjamins; 2001:1–26.

Chen T: Hànyǔzhōng chùsuǒcí zuò zhǔyǔde cúnzàijù ("The existentials with locative words as subjects in Chinese"). Zhōngguó Yǔwén ("Chinese Language") 1957, 8: 15–19.

Chen Y: Shíjiān fùcí zài yǔ zhe ("Temporal Adverb ‘zai’ and ‘zhe’"). Hànyǔ Xuéxí ("Chinese Language Learning") 1999, 4: 10–14.

Clark EV: Locationals: Existential, locative, and possessive constructions. In Universals of Human Language: Syntax (Vol. 4). Edited by: Greenberg JH. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1978:85–126.

Dai X: Guānyú Jìngtài Cúnzàijù hé Dòngtài Cúnzàijù ("About Static Existentials and Dynamic Existentials"). Yǔyánxué Tànsuǒ ("Explorations in Linguistics") 1988, 1: 82–89.

Davidse K: Transitivity/Ergativity: The Janus-headed grammar of actions and events. In Advances in Systemic Linguistics: Recent Theory and Practice. Edited by: Davies M, Ravelli L. London: Pinter; 1992:105–135.

Davidse K: On transitivity and ergativity in English, or on the need for dialogue between schools. In English as Human Language: To Honour Louis Goossens. Edited by: van der Auwera J, Durieux F, Lejeune L. München: Lincom Europa; 1998:3–26.

Dik S: The Theory of Functional Grammar. In Part 1: The Structure of the Clause, Second Revised Editon. Edited by: Kees H. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter; 1997.

Dixon RMW: Ergativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1994.

Fan F: Cúnzàijù ("Existential Sentences"). Zhōngguó Yǔwén ("Chinese Language") 1963, 5: 386–393.

Fan X: Guānyú Hànyǔ Cúnzàijùde Jièdìng hé Fēnlèi Wèntí ("On the Definition and Classification of Existentials in Chinese"). In Yǔyánxué Yánjiū Jìkān ("Paper in Linguistics"). Shanghai: Shanghai Dictionaries Press; 2007.

Freeze R: Existentials and other locatives. Language 1992,68(3):553–595. 10.2307/415794

Guo J: Lǐngzhǔshǔbīnjù ("Sentences with possessor as subject and possessed as object"). Zhōngguó Yǔwén ("Chinese Language") 1990, 1: 24–29.

Halliday MAK: Notes on transitivity and theme in English (Part 3). Journal of Linguistics 1968,4(2):179–215. 10.1017/S0022226700001882

Halliday MAK: An Introduction to Functional Grammar. 2nd edition. London: Arnold; 1994.

Halliday MAK (3rd ed. Revised by C.M.I.M. Matthiessen). In An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Routledge; 2004.

Huang C-TJ: On shì and yǒu . Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology Academia Sinica 1998,59(1):43–64.

Langacker RW: Foundations Of Cognitive Grammar (2): Descriptive Application. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press; 1991.

Lei T: Cúnzàijù yánjiū zōnghétán ("Remarks on the study of existentials"). Hànyǔ Xuéxí ("Chinese Language Learning") 1993, 2: 22–26.

Li L: Xiàndài Hànyǔ Jùxíng ("Sentence Patterns in Modern Chinese"). Beijing: The Commercial Press; 1986.

Li Z: Chūxiànshì yǔ xiāoshīshì dòngcíde cúnzàijù ("Existentials with (dis)appearance verbs"). Yǔwén Yánjiū ("Studies on Philology") 1987, 8: 19–25.

Li J: Shìlùn fāshēngjù ("On occurrence clauses"). Shìjiè Hànyǔ Jiàoxué ("Chinese Teaching in the World") 2009, 1: 65–73.

Lin TJ: Locative subject in Mandarin Chinese. Nanzan Linguistics 2008, 4: 69–88.

Lu J ("Studies of Chinese Grammar in the 1980s"). In Bāshí Niándài Zhōngguó Hànyǔ Yǔfǎ Yánjiū. Beijing: The Commercial Press; 1997.

Lü S: Zhōngguó Wénfǎ Yàolüè ("Aspects of Chinese Grammar"). Beijing: The Commercial Press; 1943.

Lü S: Cóng zhǔyǔ bīnyǔ fēnbié tán guóyǔ jùzide fēnxī ("From the difference between subject and object to the analysis of Chinese sentences"). In Kāimíng Shūdiàn èrshí Zhōunián Jìniàn Wénjí ("Proceedings of the 20th Anniversary of Kaiming Bookstore"). Beijing: The Commercial Press; 1946:1–56.

Lü S: Shuō shèng hé bài ("On win and defeat "). Zhōngguó Yǔwén ("Chinese Language") 1987, 1: 1–5.

Lyons J: A note on possessive, existential, and locative sentences. Foundations of Language 1967, 3: 390–396.

Lyons J: Semantics (vol. 2). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1977.

Peeters B, MMarie-Odile J, Patrick F, Perini-Santos P, Maher B: NSM Exponents and Universal Grammar in Romance: Speech; Actions, Events and Movement; Existence and Possessions; Life and Death. In Semantic Primes and Universal Grammar: Empirical Evidence from the Romance Languages. Edited by: Bert P. Amsterdam: Benjamins; 2006:111–136.

Peterson PL: Fact Proposition Event. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishing; 1997.

Ren Y: Lǐngshǔ yǔ Cúnxiàn ("Possession vs. Existence and (dis)appearance"). Shìjiè Hànyǔ Jiàoxué ("Chinese Teaching in the World") 2009, 3: 308–321.

Shao J, Ren Z, Li J, Rui C, Lihong W: Hànyǔ Yǔfǎ Zhuāntí Yánjiū ("Studies in Chinese Grammar: A Subject Matter-Oriented Survey"). Beijing: Peking University Press; 2009.

Shen J: Zàitán Yǒujiè hé Wújiè ("Boundness and Unboundness Revisited"). In Yǔyánxué Lùncóng ("Essays in Linguistics") (vol. 30). Beijing: The Commercial Press; 2004:30–54.

Shen J: Yǒujiè hé wújiè ("Boundness and unboundness"). Zhōngguó Yǔwén ("Chinese Language") 1995, 5: 367–380.

Shi Y: Yǔyánxué jiǎshèzhōngde zhèngjù wèntí ("On evidence of linguistic hypothesis"). Yǔyán Kēxué ("Linguistic Sciences") 2007, 7: 39–51.

Siewierska A: Introduction: Impersonalization from a subject-centred vs. agent-centred perspective. Transactions of the Philological Society 2008,106(2):115–137. 10.1111/j.1467-968X.2008.00211.x

Song Y: Lüètán "Jiǎcúnzàijù" ("Brief notes on ‘Pseudo-existentials’"). Tiānjīn Shīdà Xuébào ("Journal of Tianjing Normal University") 1988, 6: 86–89.

Song Y: Xiàndài Hànyǔ Cúnzàijù ("Existential Sentences in Modern Chinese"). Beijing: Philology Press; 2007.

Tao H: "Chūxiàn" lèi dòngcí yǔ dòngdài yǔxìxué ("Verbs of the appear type and dynamic semantics"). In Cóng Yǔxì Xìnxī dào Lèixíng Bǐjiào ("From Semantic Information to Typological Study"). Edited by: Shi Y. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press; 2001:157–164.

Vendler Z: Linguistics in Philosophy. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press/Beijing: Huaxia Press; 1967/2002.

Wang Y, Xu J: A systemic typology of possessive and existential constructions. Functions of Language 2013,20(1):1–30. 10.1075/fol.20.1.01wan

Wang Y, Zhou Y: Yǒuzìjù de lìshǐ kǎochá hé héngxiàng bǐjiào ("The you -constructions from a diachronic and cross-linguistic perspective"). Huázhōng Shīfàn Dàxué Xuébào ("Journal of Central China Normal University") 2012, 5: 91–99.

Wu X: Xiàndài Hànyǔ Cúnxiànjù ("Existential and (Dis)appearance Sentences in Modern Chinese"). Shanghai: Xuelin Press; 2006.

Yamamoto M: Agency and Impersonality: Their Linguistic and Cultural Manifestations. Amsterdam: Benjamins; 2006.

Yutaka F: Wàijiè míngcí de xiǎnzhùxìng hé jùzhōng míngcí de yǒubiāoxìng ("Cognitive salience and nominal markers"). Dāngdài Yǔyánxué ("Contemporary Linguistics") 2001, 4: 264–274.

Zeitoun E, Huang LM, Yeh MM, Chang AH: Existential, possessive, and locative constructions in Formosan languages. Oceanic Linguistics 1999,38(1):1–42. 10.2307/3623391

Zhang X: Cúnzàijù ("Existential Sentences"). Yǔyánxué Niánkān ("Annual Journal of Linguistics") 1982, 48–58.

Zhang B ("From agent-patient relation to constructional meaning"). In Cóng shīshòu guānxì dào jùshì yǔyì. Beijing: The Commercial Press; 2009.

Zhang Y: Dòngcí yǎnshēngyì hé shuāngchóng fànchóuhuà guānxì ("Extended verb meaning and double categorizations"). Wàiyǔ Yánjiū ("Foreign Languages Research") 2012, 2: 30–36.

Zhu D: Xiàndài Hànyǔ Yǔfǎ Yánjiū, ("Studies on the grammar of Modern Chinese"). Beijing: The Commercial Press; 1980.

Acknowledgements

Yong Wang would like to thank Professor Jonathan Webster for inviting him to visit City University of Hong Kong from March through July, 2012, which made it possible for him to finish the present research. Our thanks go to the two anonymous reviewers of Functional Linguistics, for their comments and suggestions. This study is supported by "New Century Talent Supporting Project, Ministry of Education, China" (Grant No.: NCET-13-0819) and "Research Fund of Humanities and Social Sciences for Young Scholars, Ministry of Education, China" (The Syntactic Realization of Sentential Categories on the Predicate-Initial Position, Grant No.: 12YJC740054).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

YW is responsible for most of the ideas in the research, including the term of event‒existential, its scope, and the semantic and functional features. YZ collected and suggested most of the examples, proposed the continuous relation between the two kinds of existentials. Both authors participated in drafting the manuscript and both read and approved the final manuscript.

Yong Wang and Yingfang Zhou contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhou, Y. A functional study of event-existentials in Modern Chinese. Functional Linguist. 1, 7 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-419X-1-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2196-419X-1-7